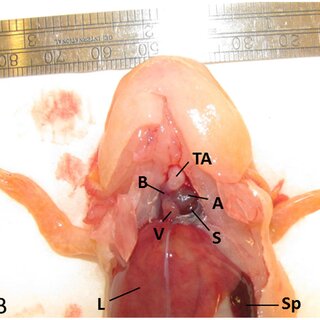

The axolotl heart may look small, but it’s a fascinating organ with unique features that make it very different from our own. Located just behind the front legs (the pectoral girdle), the heart sits safely inside a protective sac called the pericardial cavity.

Unlike humans, who have four chambers, axolotls have a three-chambered heart: two atria and one ventricle. Blood returning from the body and lungs enters the atria, while a single ventricle pumps it out. There is also an additional chamber called the sinus venosus, which collects returning blood, and an outflow tract known as the conus arteriosus. Inside the conus is a spiral valve that helps guide blood toward either the lungs or the rest of the body.

Because axolotls only have one ventricle instead of two, oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor blood mix together before leaving the heart. This may sound inefficient compared to mammals, but it works perfectly for an aquatic amphibian that takes in oxygen through both its lungs and its external gills.Interestingly, the axolotl heart closely resembles the embryonic stage of a human heart, which is one reason scientists study it so closely.

How the Axolotl Heart Works

The axolotl heart beats much more slowly than ours (which is typically 19–30 beats per minute, depending on the individual’s health, stress levels, or whether anesthesia is used in experiments). Despite this slow rhythm, the heart contracts in an alternating cycle, with the atria and ventricle working together to keep blood moving through the body.

Because oxygen delivery in axolotls is not about high concentration but rather distribution, their heart focuses on moving available oxygen efficiently to the cells that need it most. This system supports their fully aquatic lifestyle and their relatively low metabolism compared to warm-blooded animals.

Regeneration: A Heart That Heals Itself

One of the most remarkable things about axolotls is their ability to regenerate damaged heart tissue. If a piece of the heart is removed or injured, axolotls can grow it back almost perfectly.

The process is slow but steady. Within a day, a visible hole forms where the tissue was lost. After about 30 days, new muscle begins to close the gap, and by 90 days the heart is nearly restored in both structure and function. Heart cells (called cardiomyocytes) actually begin dividing and multiplying—a process that is almost impossible in adult mammals.

During this repair, the axolotl heart also changes how it produces energy, switching its metabolism to support faster healing. This combination of cellular activity and energy shifts makes regeneration possible. Because of this, axolotls are key research models for scientists trying to discover how human hearts might one day heal after a heart attack or other injury.

FAQs About Axolotl Hearts

1. Can axolotls survive heart damage?

Yes, axolotls can often survive injuries to their heart that would be fatal in most other animals. Thanks to their regenerative ability, damaged tissue is replaced with healthy muscle over time, restoring both structure and function. While the heart may initially beat more weakly after an injury, recovery is usually complete within a few months.

2. Do axolotls ever suffer from heart diseases?

Axolotls are far less prone to heart disease than mammals, but that doesn’t mean they are immune. Poor water quality, infections, or genetic issues can sometimes affect heart health. However, because of their regenerative capabilities, axolotls can often recover from conditions that would be life-threatening in other species.